“That’s so SPED.” “What are you, autistic?” “Dude, you’re mentally sick.” It’s not unusual to hear these comments passed around jokingly and blatantly in high school halls without hesitation, which proves it isn’t the awareness of mental disorders the public struggles with—it’s the understanding.

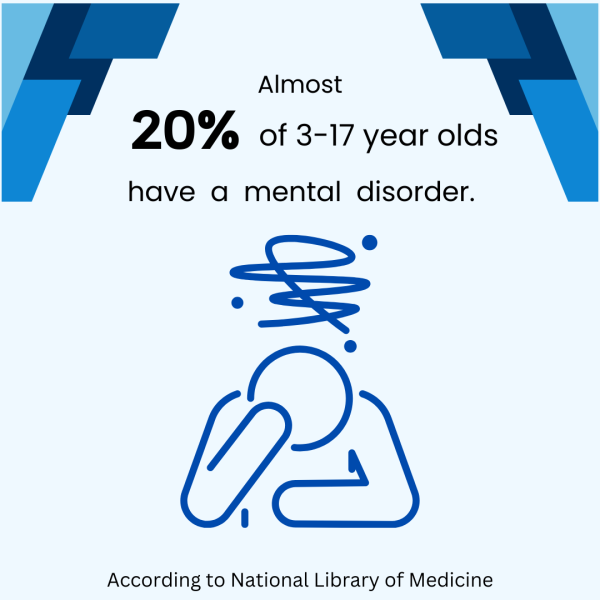

Having a mental disorder isn’t exactly uncommon. According to the National Library of Medicine, almost 20% of those aged 3-17 in the United States have a mental disorder–yet misconceptions around mental disorders are unfortunately plentiful, especially with the help of mass media’s one-sided takes on mental disorders. Common examples are that depression means constant sulking, autism means being unable to socialize and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder means hyperactiveness.

Furthermore, many well known symptoms of common disorders are visible in only one gender–either males or females depending on the disorder–leaving the other gender severely undiagnosed, especially if gender norms and stereotypes seep into one’s perception.

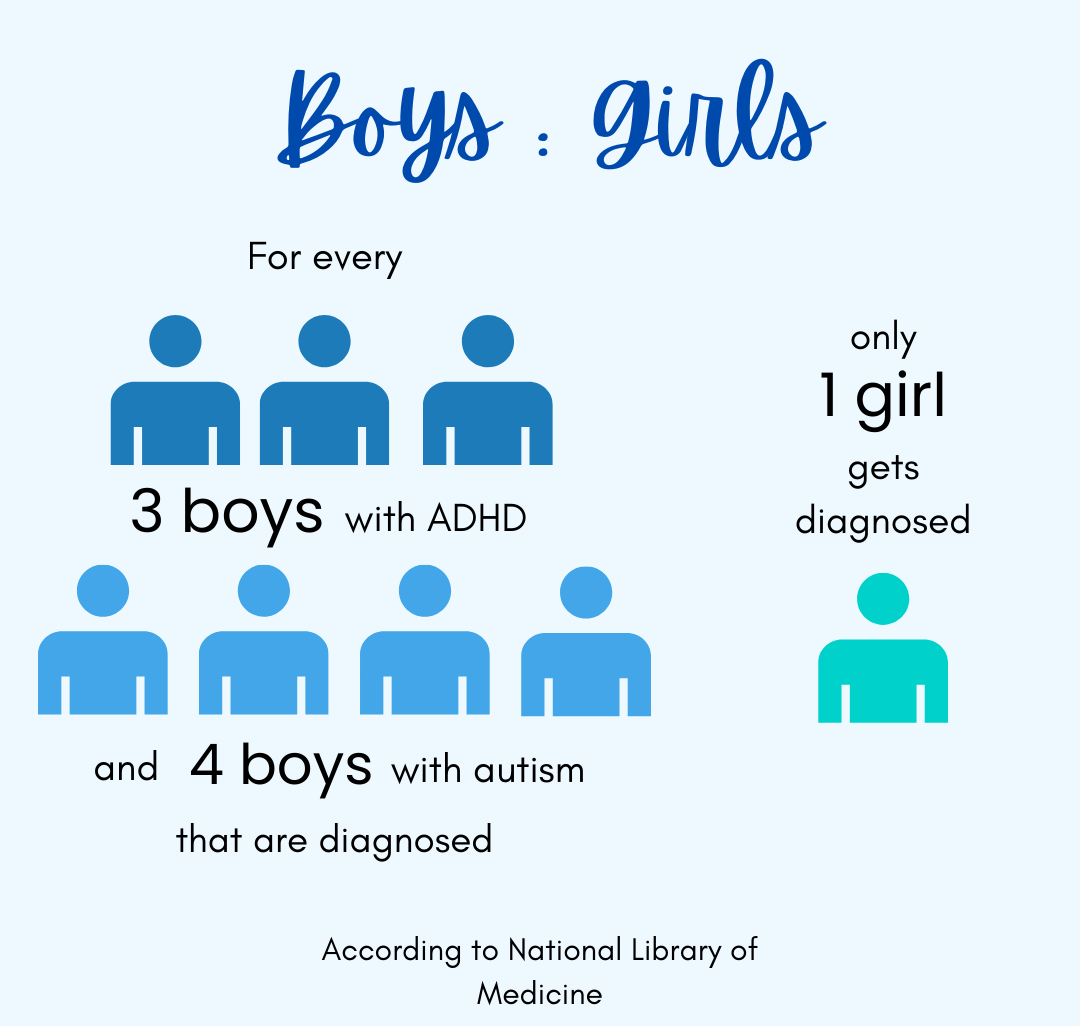

For example, boys are three times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than girls. According to Children and Adults with ADHD (CHADD), boys tend to display behavior such as hyperactivity, more noticeable and more directly associated with ADHD. Female symptoms, however, tend to be more inward, such as being over-talkative and having problems staying organized and focused, causing these symptoms to commonly end up ignored.

It’s the same situation for autism, or more specifically, Autism Spectrum Disorder, containing a variety of disorders that include repetitive behaviors and social communication difficulties, as boys are four times more likely to be diagnosed than girls.

For both autism and ADHD, girls can mask their symptoms and might work harder to “be normal.” The result is being “assessed as not needing help”, according to CHADD. Symptoms are also attributed to gender stereotypes and character flaws, according to Foothills Academy Society. Symptoms are also commonly “viewed as irresponsibility or a poor work ethic” and all in all, the disorders show up as anxiety, depression or low self-esteem, persisting into adulthood and causing more problems, according to Cedars Sinai Medical Center.

Depression, another common disorder among teens, is more complex. Girls are thought to fall victim to depression more often than boys, which is true, but there are still many warning signs in boys that are missed because of how much they stray from the “norm.” While feelings of hopelessness are the same, boys tend to show anger instead of crying and eat much more instead of eating less as girls do.

Teens are also increasingly surrounded by gender norms, especially males, by the idea of being “tough” as they grow and become less inclined to show signs of weakness, like sadness or crying, according to National Library of Medicine. But many symptoms are downright ignored, regardless of gender, often attributed to mood swings or acting out.

However, underdiagnosing is just one of many problems. While these perspectives aren’t entirely wrong, they are extremely one-sided and unrepresentative, creating stereotypes about disorders that show why one has, or more commonly can’t have, a mental disorder.

The way society incorporates awareness about these disorders can also be harmful and insensitive. The movie “Joker,” for instance, stars a comedian who turns into the renowned villain and is widely believed to be affected by the pseudobulbar affect, in which those who have it can randomly start laughing or crying uncontrollably. There’s also the way people, especially teens, use specific words used as slang words as insults. Some common ones are “mentally sick,” “autistic,” “on the spectrum”–a reference to autism–and “SPED,” standing for special education.

Awareness isn’t the same as understanding; it isn’t enough. Understanding means caring, not just acknowledging. It doesn’t just mean knowing what mental disorders commonly look like. It means knowing they aren’t a one-size-fits-all or show as stereotypes since they can show differently across different ages and genders. Awareness means knowing what it looks like when someone has a disorder. But understanding means knowing that they’re so much more – not characterized with a single slang word.