Overcrowding creates congested educational environment

On Sept. 7, almost every seat in the cafeteria is filled with students.

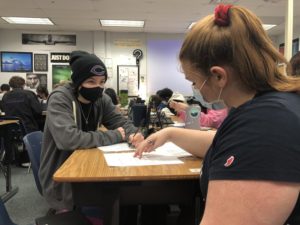

Cars cram bumper to bumper during morning drop-off and bus drivers are forced to turn away students. Bodies jostle against each other in tight corridors as they travel to small classrooms that have every seat filled. Empty lunch tables are scant.

From the moment students arrive at school, they are faced with the issue of overcrowding. As they return to the building this school year, many feel as if classes have suddenly doubled in size.

“[In] my math class and my language of medicine class, there’s 35 to 40 people,” sophomore Vishal Narayan said. “Every single desk is taken, so there’s no space.”

While students may be quick to blame the crowded school on high student enrollment after a full return from the pandemic, the number of people at CHS is actually a little bit lower than last year.

This year, there are 2,905 students physically attending the school. At the beginning of last school year, there were 2,932 students at school. It’s not a difference in the number of students from last year that is the root of the issue.

“Chantilly, as a high school, is over capacity,” director of student services Amy Parmentier said. “The physical space wasn’t designed for the number of people we have [today].”

Crowded classrooms are a result of greater deviation in class sizes this year. Class sizes can depend on the difficulty of a class, the number of teachers qualified to instruct the course and student interest, as popular classes may be extremely full while less popular classes may not. Less advanced classes, such as freshman English classes, tend to have smaller class sizes compared to advanced level classes like AP Calculus BC. This is due to the administrative presumption that students in lower level classes may require more guidance to be successful, while more advanced students have the capabilities to learn independently.

“The central office of Fairfax County Public Schools determines every school’s staffing and they do it based on what class sizes should be, and that then drives your number of teachers,” Parmentier said. “And so, our ability to change our staffing is really limited.”

Although CHS is starting the year fully staffed, the same cannot be said about bus drivers around the county. Since students returned to the building last year, there has been a bus driver shortage, and with that comes buses full of students. Forced to do double routes, many drivers arrive at school later than they should. This problem is only exacerbated by the daily morning traffic, which can be attributed in part to the school only having two entrances.

“When my bus arrives in the afternoon, there’s usually a huge crowd of people rushing towards the entrance, pushing and shoving each other to avoid having to sit three to a seat,” junior Rhea Rajmanna said. “Eight or nine people end up being the third seater and basically have to sit halfway in the aisle.”

In the past 50 years, the population of Fairfax County has doubled, coming in at 1,170,033 people in 2021, contributing to the gradual urbanization of the region. Even so, plans for a new high school in the western side of the county, which would lessen the number of students in various Fairfax County schools, have not come to fruition. Funding is going toward new elementary schools; however, the county is currently looking for a location for the new high school. Schools are then forced to grapple with the staggering numbers by crowding their classrooms.

“When Chantilly was built, it wasn’t built for 2,900 people,” Parmentier said. “When you’re walking through the hallway, and it feels overcrowded, it’s because it is.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Chantilly High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our printing and annual website hosting costs.

Haley Oeur is a senior in her third year with The Purple Tide. She loves walking into random clubs, and is part of the quiz bowl team, Reader's Club, Photo...