A rough match

Athletes take on toxicity throughout team tryout season

Illustrated by Rachel Neathery

Exclusion in team sports is a form of relational harassment, a form of bullying in which a student aims to damage another athlete’s relationships or social status. A 2014 Brigham Young University study found that bullying during sports-related activities caused students to develop a lower physical-health quality of life, with bullied students engaging in athletic activities less regularly– usually even after one year.

March 27, 2023

With their shoes laced up and t-shirts slipped on, students of all skill levels raced to the field as tryouts for spring sports teams began on Feb. 20. Although tryouts aren’t new for many, they can be difficult for students who are the victims of sports-related bullying from peers throughout the year.

“When people make fun of me for trying out for sports, it makes trying out a little more daunting,” freshman Madhavan Kandagatla said. “Even though sports might just be a hobby for some of us, we all have ambitions, and people shouldn’t make fun of us when we are trying to do our best.”

Many students opt to start training for tryouts weeks in advance, and will attend preseason conditioning sessions for their specific sport. These sessions give athletes the chance to take part in exercises related to their specific sport. However, these sessions can also open the door to negative interaction between students.

“During tryout preparation, other students have said discouraging things to me in the locker room and on the field,” a sophomore who tried out for soccer said. “They’ve given me weird looks and pick on those of us who are a different race or just not very good at the sport, and it’s made me uncomfortable.”

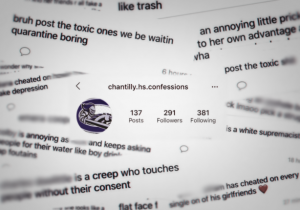

According to Research Gate, the prevalence of bullying in team sports is 26.7%. Verbal harassment is the most common form of bullying, according to Stomp Out Bullying, and can extend from name calling or taunting to threats of violence toward a teammate. Many athletes also face relational harassment, which is where teammates gossip about them or embarrass them in front of others both in person or online.

“I remember when I said I was going to try out for track, people would come together to tell me in person and on social media that there was no way I’d ever make the team,” Kandagatla said. “They would also make fun of my height a lot, and they called me names even though I didn’t say anything mean to them.”

A poll taken of 50 CHS athletes between Feb. 17-21 found that 24% of students had faced harassment from other students as they prepared for tryouts. The students reported that others made fun of their weight and abilities, made them feel uncomfortable and influenced them into believing that they wouldn’t succeed on a school team. Some of the students surveyed said that the harassment ultimately swayed them into not trying out for a school sport at all.

“I try to make sure that I don’t let them get to me, but their behavior has caused me to avoid drawing attention to myself, or else they might say or do something that makes the situation worse,” the soccer athlete said.

Although sports-related bullying is a subset of bullying as a whole, it is less researched and reported less frequently than other types of bullying. This can be attributed to the fact that student athletes and coaches often do not emphasize or even encounter the harm of bullying, according to the National Library of Medicine. Instead, coaches may adhere to the belief that athletes should use their negative emotions as a way to motivate themselves to perform their sport more effectively, further prompting bullying to be left alone in school sports.

“There’s also probably an element of courage needed to speak out against harassment during tryouts, because many students do not want to create drama within the team and are also afraid of retaliation from other athletes,” Physical Education Department Chair Carmen Wise said.

Wise, who helps manage and direct school activities as well, was surprised that harassment had been taking place during the tryout season.

“Nobody has told me about this,” Wise said. “That’s why somebody needs to take initiative, whether it’s the victims, bystanders or even a friend, because that’s the only way we’ll know that something is going on and be able to address the problems that our students are facing.”

On their official website, Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) states that when bullying is reported, school administrators and counselors will work to ensure that the students who bully understand the consequences of their harmful behavior. Simultaneously, they say staff will work toward helping the victim feel safe and supported by teaching them other ways to handle the bullying. FCPS, like Wise, adds the importance of having bystanders report inappropriate behavior.

“Honestly, I still don’t have faith in any administrator or coach to change anything,” the soccer athlete said. “Nothing has been done so far so I don’t know what they’re actually going to do, but even then, I don’t feel sorry for myself. And I think that’s important for everyone to know, that harassment is not going to necessarily stop me from going for it.”

As Very Well Family states, athletes should empower themselves by either standing up to their bully in the face of sports-harassment or simply ignoring their bully and instead focusing on the skills they have. Individuals, they say, should not feel apologetic for not fitting the standard of others.

“When I play, I remind myself that I don’t play for them: I play for the sport,” Kandagatla said. “Whatever insults they throw, I do my best to take them from a negative to a next level positive.”