All schools share the same objective: to provide the best education for their students. Yet, despite this shared central goal, the path to giving this education– through their grade policies– differs between each district, school and teacher.

Inevitably, schools within districts develop variations in their grading policies. For example, while some schools may implement midterms and finals, others do not. The way districts approach testing deviates even further, with many schools implementing retakes and extra credit, while others do not implement more policies that give more advantage to college applicants than others.

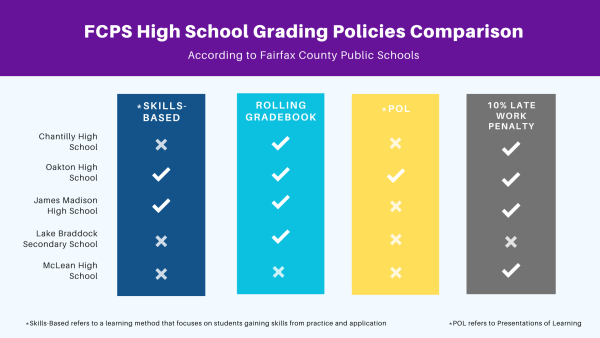

For example, high schools within FCPS have slight distinctions in their grading policies. Compared to Chantilly High School’s knowledge-based learning, Oakton High School along with James Madison High School uses skills-based learning– focusing more on action and skill-building. Additionally, for OHS, Presentations of Learning are implemented at the end of the year, constituting half of a student’s English or Social Studies final exam.

Individual teacher grading variations present another example of inconsistency. As of 2023, there were 3.8 million teachers across 98,755 schools in the United States, each teacher having diverse backgrounds which include education, ethnicity and religion– all of which can play into each teacher’s diverse way of grading.

Inconsistencies in grading may also be caused due to a teacher’s emotional state. According to a study done by Theory and Practice, emotions may play a role in the grades teachers assign. The study states that harsher or softer grades can be a result of an educator’s emotional state, along with the addition of more lenient grading toward students that the teacher has a level of fondness for, giving a greater disadvantage or advantage for students.

Grading discrepancy can also come from a teacher’s qualifications. The two main ways to measure a teacher’s qualifications are through their education level and teaching experiences. While a majority of teachers have a postsecondary degree and certification in their respective primary subjects, some do not, creating an extra variable in grading. According to a study by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, teachers who had more experience had higher grading standards– along with educators who graduated from more selective and prestigious colleges, presenting disadvantages for more college applicants compared to others.

These disparities and inconsistencies display the overall decentralized system of American Education. Since there is not a standard grading rubric, the way schools grade varies from location to location. Although this decentralization can be beneficial to some, it overall yields inaccurate measurements of a student’s academic achievement– even possibly misrepresenting the extent of an achievement.

Fairfax County Public Schools has an A range of 93-100%, weighing 3.8-4.0. However, Loudoun County Public Schools, unlike FCPS, has an A+ range from 98-100%, weighing 4.3. Similarly, there are slight point variations in what defines a letter grade, such as the F letter grade in LCPS being 59% compared to FCPS’ 63%; a disadvantage for FCPS students.

The differences in the grading policies across FCPS high schools lead to differences in GPAs for a similar quality of work. This holds importance, as according to the National Association of College Admissions Counselors, high school grades were of considerable importance 74.1% of the time, giving more advantages to some college applicants.

To address grading inconsistencies, there should be the normalization of teacher periodic check-ins with other teachers in their departments to maintain objectivity in grading non-objective assignments. This can be complemented by a clear, standard rubric for each subject from the United States Department of Education.

With the push of increased resources for self-awareness, teachers can recognize and reduce the influence of externalities on grading decisions to best ensure grading equity for all students.