The “CNN effect” dominated discussions about U.S. foreign policy in the 90s. The introduction of the world’s first 24-hour television news network, which allowed American citizens to watch war live during the Gulf War in 1991, was alleged to play a big part in public opinion on foreign policy and subsequently influence policymakers’ decisions.

This effect is simply another example of a truth that has held up for centuries: the media strongly influences public opinion. Exaggerated versions of Pope Urban II’s 1095 speech caused the Crusades. Yellow journalism created a tense climate that resulted in the Spanish-American War at the end of the 19th century. Very famously, antisemitic propaganda led to the Nazi regime in the 1930s.

While 24-hour TV news networks were revolutionary for their time, today, the world faces a new kind of media: social media. One-quarter of U.S. adults often got their news from social networking sites in 2024, a number that has grown steadily over the past few years. Yet the introduction of unprecedented access to worldwide news hasn’t translated to more Americans following international affairs—71% of polled U.S. adults consume little to no foreign news every day, while 63% consume at least 30 minutes of U.S. news a day.

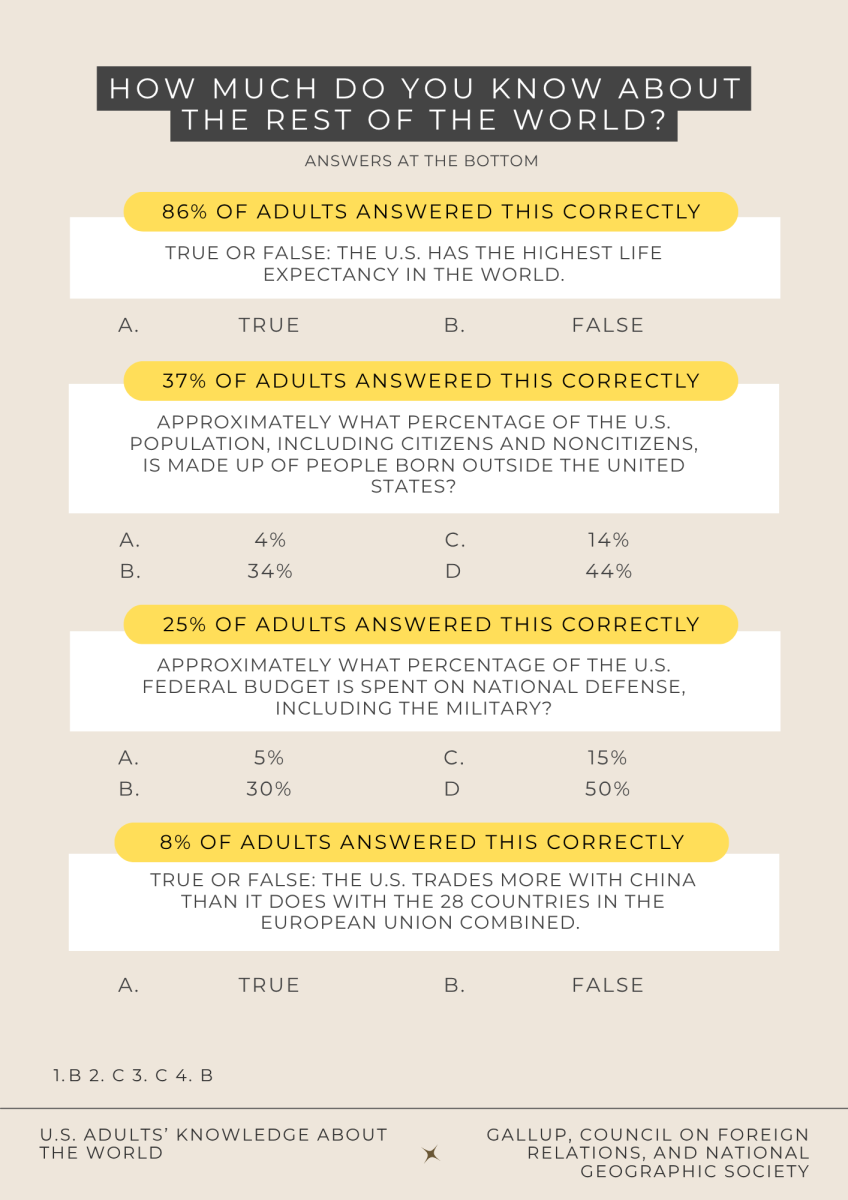

This has led to greater ignorance of the world outside of America’s borders. In 2019, a paltry 6% of American adults scored 80% or higher on a Gallup survey concerning world affairs and geography. What’s more, the number of Americans who believe the U.S. is better off when it plays an active role in world affairs has also fallen, from 70% in 2018 to 56% today.

That last statistic is particularly concerning. It seems that the gradual erosion of American exceptionalism has followed the rise of social media. American exceptionalism is the idea that the U.S., in its superiority and uniqueness to other countries, bears a moral responsibility to promote and uphold democratic values and personal freedoms throughout the world. This idea has, in large part, driven U.S. foreign policy for the last 80 years; President Harry S. Truman’s Truman Doctrine, a prominent example of American exceptionalism in foreign policy, has influenced many of Truman’s successors.

Social media has played a tremendous part in this growing American indifference to the rest of the world. Algorithms create the well-documented “echo chamber effect,” in which users are fed similar content over and over, resulting in a lack of exposure to diverse perspectives. Meanwhile, users are inherently drawn to content that feels personally relevant to them, and thus often feel little incentive to try and diversify their content.

Some may argue that there should be little concern over the fact that Americans don’t pay much attention to the rest of the world—after all, they say, Americans should only be concerned about the news and policies that will affect them.

This sentiment is wrong. A large part of the American economy depends on international trade, so changes in other countries (i.e., political instability, economic downturns), especially ones we trade with, would have negative impacts on the U.S.’s economy. Foreign countries’ changes in climate and immigration policies also affect the U.S., as well as foreign conflicts and wars. It’s important for Americans to be aware of what’s going on elsewhere because those things do directly impact them.

This sentiment is wrong. A large part of the American economy depends on international trade, so changes in other countries (i.e., political instability, economic downturns), especially ones we trade with, would have negative impacts on the U.S.’s economy. Foreign countries’ changes in climate and immigration policies also affect the U.S., as well as foreign conflicts and wars. It’s important for Americans to be aware of what’s going on elsewhere because those things do directly impact them.

Moreover, the concept of American exceptionalism, while some consider it arrogant, holds true. America, as an exceptionally well-off country, has a moral responsibility to promote and support the well-being of other countries. Not only is it the right thing to do, but helping the rest of the world out will boost global markets, which in turn enriches individual countries’ economies and continues the chain of prosperity.

The solution is not that simple, though. Social media companies have proved time and time again how hard it is to get them to change their algorithms. While our government should continue to push these companies to make proper reforms, some of the responsibility in becoming better informed lies on the American people themselves. After all, our social media feeds are originally based on our own biases. Americans must make a greater effort to fight back against the social media algorithms and diversify the news content that they follow, not only for the U.S.’s sake, but for the rest of the world too.