How Chantilly has evolved through the years

November 14, 2019

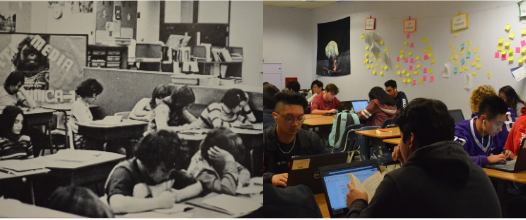

Naming what makes Chantilly exceptional today is hardly difficult. The Governor’s STEM Academy presents rare skill-based learning opportunities to students. The newly installed Innovation Lab provides the community with access to the latest technological advances. The soccer field and crimson track offer the school’s winning sports teams a place to demonstrate their superior athletic talent. But what did Chantilly look like in its early years, before its prominence?

In the 1960s, an unconventional way of learning became a widespread trend in education: open classrooms. The concept of an open classroom is characterized by an absence of walls to separate it from other classrooms. When Chantilly was built as a secondary school in 1972, it was one of many open classroom schools around the country.

“There were no true walls,” English Department chair Mary Kay Downes said. “The whole concept, which has been totally discredited, was that people can learn from being in close communities with one another.”

The open classroom trend was originally an outcome of the hippie movement that dominated the 1960s. The counterculture movement, which emphasized cooperation and free thinking, easily incorporated the notion of free-flowing learning. The idea was that young people should be able to learn about what they like in an interactive, unstructured way without being limited by physical barriers.

“One of the theories was, with open classrooms, teachers would communicate more with one another,” physics teacher George Dewey said. “Maybe a teacher would hear what plans were going on in the other class that would influence their class in a positive way. It really did enrich what we were doing.”

After several years went by, it became difficult to ignore the challenges posed by the open classroom structure. Students faced constant distractions from other classes and teachers struggled to stick to their individual lesson plans.

“I started teaching at Chantilly in 1987. By the time I got there, they realized that the open classrooms wouldn’t quite work,” Downes said. “So they had a number of these cabinets, and you would have those along with barriers, and they would divide areas.”

When English teacher Mike Murphy attended the school in the 1980s, every classroom was separated by these semi-partitions, which rose about halfway to the ceiling. But they didn’t solve the issue of nearby distractions for students.

“Some of the partitions were only chest-high, and if you stood up you could see all the other classes. It was crazy,” Murphy said. “You could sit in the back of a classroom and talk to people in the next classroom behind you because there were gaps in the walls. You could pass notes back and forth if you felt like it, or throw a paper airplane into the next room.”

Students weren’t the only ones who had trouble working in this environment. The partitions also didn’t fix the hardships open classrooms presented to teachers.

“If a teacher wanted to show a motion picture and turn down the lights for it, all of the lights in adjoining classrooms went out too,” Dewey said. “You’d be teaching a class and all of a sudden the lights would go out. That did not sit very well with other teachers.”

In the early 1990s, the school was finally renovated. Walls were built to separate every classroom, and new additions were made, including the library and windows around the school.

“It was like a crowded city street. It was more fun in some ways, but also just more frustrating,” Murphy said. “There wasn’t a lot of pride in how the school was set up. The library right now is beautiful. You can’t wait to go there. None of that was going on [in the 1980s].”

It can be easy to lose sight of what happened in the past for places and people to become what they are now. Students and staff can acknowledge the history of the school and take pride in the changes that created the Chantilly we know today.

Steve • Sep 23, 2022 at 6:37 pm

The original building was falling apart. The original plans would have left the school falling apart until the early 90s. It was the students of the classes of ’88, ’89, ’90, and ’91 who fought for change. In spring of 1988, there was a student sit-in that lasted most of the day. The principal asked us to meet with him to discuss the situation. Shortly after, CHS was slated to be rebuilt. The new building was not complete until 1992 or 1993.