Missing, Murdered, Forgotten: Native American women victim to high crime rates

Native American women have endured high disappearance rates, domestic abuse, and murder.

October 28, 2020

One day they’re here, and the next day they’re never seen again. This is what life is like for many Native American women. For decades, these women have endured high disappearance and murder rates, impartial and insensitive data regarding these cases and high domestic violence rates.

According to an independent report discussed by Hon. Ruben Gallego, 5,712 Indigenous women disappearances and homicide cases were reported in 2016 alone. Of all disappearance and murder cases, 74% do not have any public record detailing whether a suspect was found or how the victim died, according to NBC News. This ongoing crisis occurs in all parts of the U.S, especially in Native American reservations.

“When news isn’t spread around, people won’t talk about it,” sophomore Anna Dimaiuta said. “When it doesn’t affect them personally, people tend not to see the issue at its full capacity.”

Miscommunication between federal tribal governments, racial bias and misclassification has led to gaps in information regarding disappearance and murder cases involving Indigenous women. When Indigenous experts Abigail Echo-Hawk, director of Urban Indian Health Institute, and Annita Lucchesi, a doctoral student, asked for information about these cases, they were met with partial and unreliable details in 60% of their interactions with cities and police departments, according to NPR. Moreover, not a single agency on the federal level has proper data on the number of missing and murdered Indigenous women, opening up the possibility of even more unreported or uninvestigated cases.

The lack of sensitivity and urgency from law enforcement when dealing with Native American cases has contributed to the rise of movements advocating for Indigenous rights. One prominent movement is the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) movement.

“I believe that movement[s] [are] very important to shed light on innocent people going missing, being murdered and being mistreated by society,” Dimaiuta said.

Some of the MMIW movement goals include helping the families of murder victims cope, bringing the missing home, providing self-defense lessons and eventually eradicating the problem. As reported by Cultural Survival, a group of Indigenous people located in Canada called The First Nations Women and Families, encouraged the Canadian government to start a national inquiry in 2015. This encouragement helped rally similar groups to do the same in the U.S.

The hashtag of #MMIW and social media presence was started by the former Grand Chief of Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak Inc. This is a non-profit group working with the Indigenous people of First Nations to provide protection and sustain strength for Indigenous people.

“The injustice Native Americans have faced is just sickening, and you don’t have to be an expert to know that,” said sophomore Dorothy Phillip.

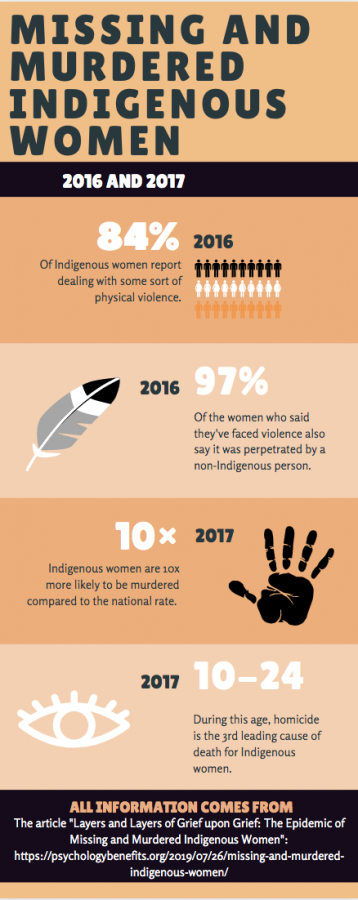

Indigenous women are not only going missing. According to Cultural Survival, Indigenous women are 2.5 times more likely to become victims of violent crime compared to other races.

Additionally, the rate of Indigenous women being murdered is 10 times higher than the national average.

“America is quoted ‘The Land of The Free,’” Phillip said. “I think it’s quite hypocritical if we, the privileged and people in power, continuously let Indigenous [people] and people of color get abused.”

The high rates of missing and homicide cases have many possible factors. According to Futures Without Violence, Alaskan natives and American Indian women have a 17% chance of being stalked in their lifetime and are most likely to report an assault from an intimate partner belonging to a different racial group.

The isolation of some reservations contributes to a lack of medical care and resources these women can receive after being attacked. Because this is a nationwide issue that goes largely unnoticed, some students feel that it is important for awareness to be spread and motivate others to speak out.

“Silence is complacency, and your complacency tells the world that you are perfectly okay with the horrific systems in place today,” sophomore Hannah Moghaddar said. “You would have fought for your rights too if they were being dismissed [in] your own home.”

Linda Banks • Nov 1, 2020 at 11:26 am

Jada’s great writing opened my mind & heart to this ongoing abuse of the powerless in the world today. Great job & much appreciated closing with corrective actions underway that I can support! I believe I will see Jada on Journalistic TV in the future! Great success!