School-to-prison pipelines run through America

Disciplinary help from the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments.

June 27, 2021

For the underprivileged, school can either be a road to a bright future or a prison cell. According to Nancy A. Heitzeg, this is due to the impacts of hyperbolized hysteria concerning youth violence. This stems from the media’s over-exaggerated display of minority youth violence in low-income areas. According to Education Not Incarceration, a multitude of students, primarily minorities, are impacted, spending their teen and sometimes adult years incarcerated.

“[A] long term effect [of the school-to-prison pipeline] could be [victims] having to catch up later in life due to [them being] left [out] at such a young age,” junior Aaliyah Wilkes said.

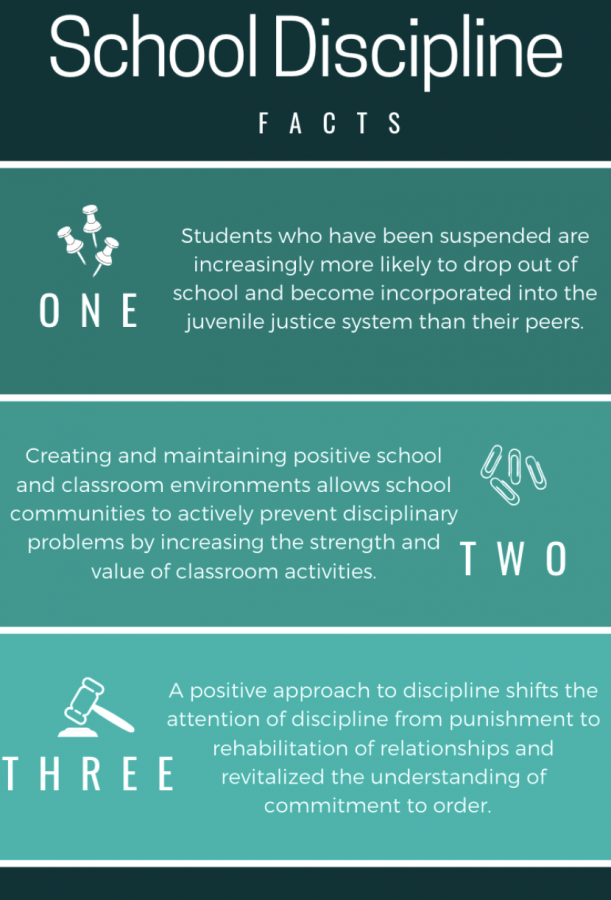

The school-to-prison pipeline is characterized as the connection between juvenile detention and school discipline. According to the Justice Policy, even though juvenile crime rates are decreasing, out-of-school suspensions have increased around 10% since 2010. Schools are no longer taking minor correction steps, but rather enforcing extremely strict repercussions.

“Students are too young to be facing such consequences,” sophomore Lydia Cha said. “Students are called students because they are meant to learn as they grow [and not]slapped in the face with a long-term [punishment].”

The school-to-prison pipeline is mainly enforced due to the implementation of zero-tolerance policies. According to Heitzeg, the rhetoric used in this policy, which is borrowed from the War on Drugs campaign, is often described as using absolute punishments for school rule violations regardless of context. Zero-tolerance policies conduct random locker and person searches, security cameras, increased police presence and metal detectors.

“[Students] may continue [making] mistakes because the type of punishment [they] receive only [makes] them more upset and feel [as if] there [is] no hope for them,” Wilkes said.

Additionally, the school-to-prison pipeline disproportionately affects minority students. According to the National Education Association, students that are of color, have disabilities, are LGBTQ+ and/or are English language learners are more inclined to face harsher punishments for the same offenses as their privileged counterparts. This discriminatory practice generally stems from America’s long history of oppression, but specifically from another phenomenon: the prison-industrial complex.

“Since many principles from our system transfer into our education system, it wouldn’t be surprising to see minorities being targeted, even as students,” Cha said.

The prison industrial complex is defined as the combined interest of the government and industry to use imprisonment, policing and surveillance as solutions to economic, social and political problems, as reported by Critical Resistance. Because minority citizens are often characterized as dangers to society, they are the primary victims of this matter.

“To break this cycle of [harsh punishment] for minority [students] would be something most people would not consider since it’s been [this] way for so many years,” Wilkes said.

In 2014, Fairfax County Public Schools adopted policies to end the zero-tolerance policy in their schools as reported by WTOP News. Other measures to prevent unnecessary punishments include limiting arrests in school, training teachers to use lenient disciplinary methods and using home and school interventions to improve student behavior.

“[The school-to-prison pipeline can impact not only [students] futures and careers but [also their] mental health and self-esteem as well,” Cha said. “As young and impressionable students, being charged with hefty punishments can be detrimental.”