Toxic positivity negatively impacts mental health of teens

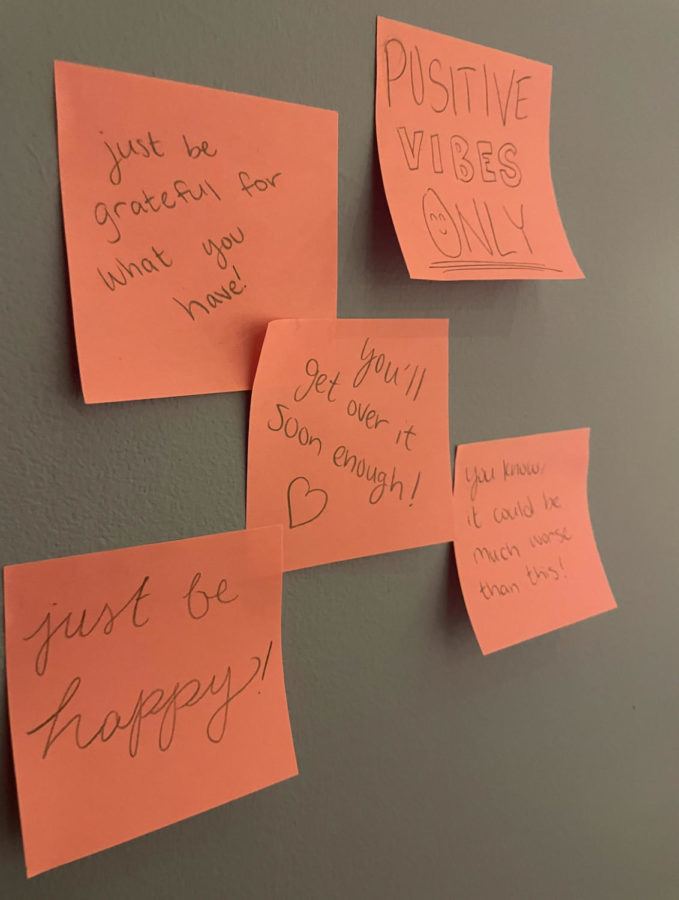

Backhanded comments like “just be grateful” or “choose happiness” only fuel toxic positivity and invalidate those who are struggling.

September 29, 2021

“Turn that frown upside down.” “You’ll get nowhere in life with all that negativity.” “At least you don’t have it as bad as others.”

These are the common, conventional remarks people receive when they are unhappy. The comments demonstrate toxic positivity, the act of dismissing negative emotions and preaching to “just be happy with what you have.” Although the intent is good, the result differs.

“When people see [others] struggling, they say ‘just be happy’ or ‘do this one thing, and you will instantly be better,” junior Connor Kentfield said. “However, anxiety and [suicidal thoughts] are a lot more complicated than they seem to be on the surface.”

People who struggle with mental health already face stigma, and comments like “choose happiness” often belittle or undermine the issues these individuals face. The goal may be to cheer someone up, but instead, toxic positivity only brings shame to a person who is struggling.

“Sometimes when I’ve struggled with my mental health, I was told ‘you used to be so positive, so why can’t you keep being positive right now?’ or ‘don’t ruin this moment by being so glum,’” sophomore Rory Ketzle said. “It hurts internally to feel like you’re hurting other people by not meeting their standards [of happiness].”

With social media’s recent push of the phrase “choose happiness,” many teens have felt that their struggles have been invalidated. If solving problems is as simple as choosing to be happy, then those teens just do not try hard enough. Additionally, the online presence of content creators, who often experience pressure to display only the pleasant parts of their lives, contributes to the want of many teens to just be happy. Because of this, teens also tend to only show the bright sides of their lives, such as adopting a new dog or spending a day at the beach, when in reality, they may be struggling.

“[On social media], I’ve seen people [who] have posted acting like they’re okay, but when you actually talk to them, you realize that they are not actually okay,” sophomore Tala Al-Hasani said. “Everyone just pressures you to be okay, especially in school, which adds an extra weight when everything is already stressful.”

If someone struggles with their mental health, telling them to “stay positive” won’t help. Other ways to comfort and help a friend or classmate who has expressed these negative feelings, besides brushing them off with superficial phrases and mottos, exist. Being there for someone without forcing them to be happy is one of the most helpful things a person can do.

“I think people [tend to believe] others are faking [bad mental health],” Kentfield said. “No matter who it is or what they’ve done, if someone is feeling suicidal, others should try to reach out and help them because one day they might be gone. We should really take the time to look after and care for the people we love.”

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, reach out. Call The Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text the Crisis Textline at 741741.