FCPS’ AAP program inherently racist, classist

March 19, 2022

Across the country, gifted and talented programs exist for the broad purpose of nurturing the minds of talented youth. Still, these programs bear the history of racism, and, thus, perpetuate it into the 21st century, creating lasting effects for the coming generation.

In third grade, I transferred to a new school to join an elite class of “advanced” students. My base school had a large Hispanic population. Despite my new school also having a large Hispanic population, my class was strikingly different in terms of demographics with most students being white or Asian-American. As one of the few Hispanic students, I felt something was very wrong. I see now that this separation is all too similar to the overt segregation that continues to plague this nation.

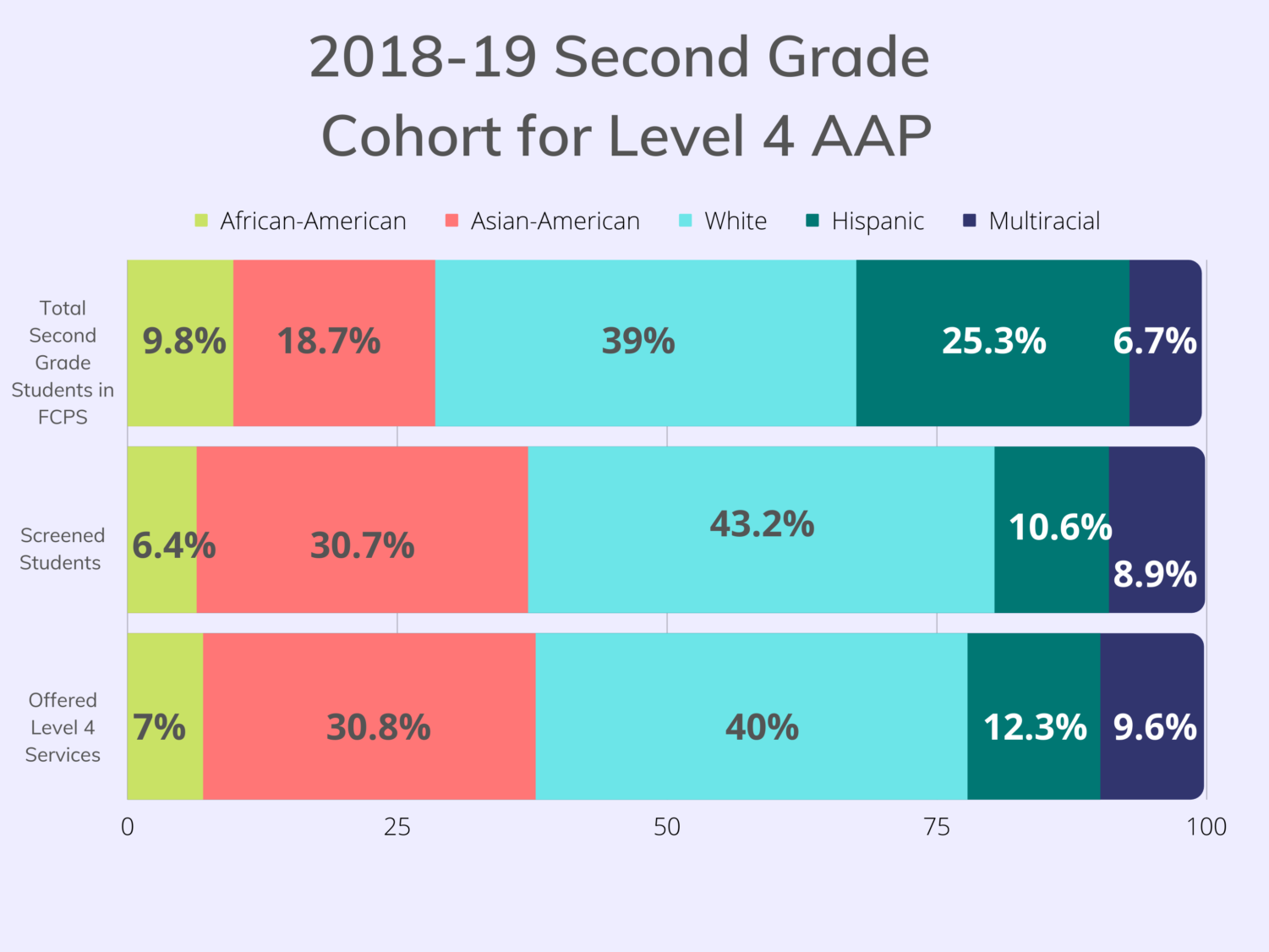

FCPS’s gifted model, Advanced Academics Program (AAP), has four levels. Level 1 service is given to all first through sixth graders and is designed to teach critical and creative thinking. Levels 2 and 3 are part-time school-based services. Level 4 is a full-time challenging program meant for students who exhibit giftedness.

In order to be eligible to be screened for Level 4 AAP, students must either score in the top 10% of their class on the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test and the Cognitive Abilities Test or be referred by their parent/guardian (about 70% of screened students are identified through referral).

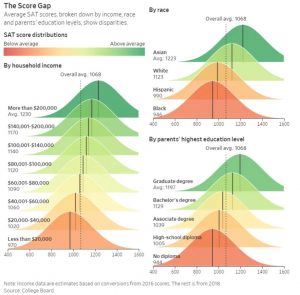

Parents who are aware of the test and have made it an objective to get their child into AAP can hire the services of a variety of test prep providers who can also coach parents on what exactly they need to do to put their child in the position to be admitted into the program. These paid services are only available to those who can afford them, ensuring that wealthier students have an advantage over their less privileged peers. A study published in the Harvard Educational review found that wealthier students are 6 times more likely to be identified as gifted compared to their low-income counterparts.

Students are then selected for full-time Level 4 through the compilation of a portfolio which includes a referral form, test scores, the Gifted Behaviors Rating Scale (GBRS) with commentary, progress reports, parent questionnaire, work samples and additional optional information. The portfolios are then sent to a committee of six individuals with varying expertise and four have to vote in favor of the child to offer admission.

In third grade, students begin Level 4 AAP; those whose school did not offer full-time services are bussed to the nearest school that does. Level 4 AAP students are guaranteed these services until the end of eighth grade.

From third to eighth grade, students are separated and told that the classroom they are placed in determines their intelligence and potential. The message delivered to students receiving general education was very clear: you are not as smart as they are. As for AAP students, the expectation of high achievement that the program sets creates an environment in which success is the only option.

High school AP and honors classes are filled with AAP kids. While those students who were not in the program are still affected by the adverse messaging given to them in their formative years, it is not impossible to succeed in high school if you were not in the program. It has been done and will continue to be done, despite all the negative messaging they received as children.

African-American and Hispanic students are underrepresented in level 4 AAP. Researchers at Vanderbilt University have found evidence to suggest that an increase in minority teachers would cause an increase in minority student placement in gifted programs. The teacher referral is an important component of the screening portfolio. Additionally, teachers serve as the closest point of contact parents have with their child’s school and can make the AAP program known to the parents of minority students.

In order to combat the underrepresentation of minorities, FCPS has implemented the Young Scholars program and the Twice Exceptional (2e) program meant to increase AAP representation of students from historically underrepresented groups and students with special needs, respectively.

However, these programs do not address the effects of separating children. The school district needs to make it a little easier for future students to be successful by making sure each child knows they are talented.

Parents are oftentimes the most important factor in decisions involving gifted and talented programs. Last year, Thomas Jefferson High School of Science and Technology, the number one high school in the country, implemented a new admission policy meant to be more equitable.

The old admission policy consisted of three phases, making the applicant pool smaller at each stage. To be considered eligible a student must have a 3.0 GPA in core class, be at least in Algebra 1 and pay a $100 dollar fee or receive a fee waiver. To progress to the next stage, a student must receive a minimum percentile score on the Quant-Q, ACT Aspire Reading and ACT Aspire Science. Those who meet that threshold must fill out the Student Information Sheet, provide 2 teacher recommendations and respond to a problem-solving essay. Then all those factors are taken into consideration for admission decisions.

Students whose parents want their student to be admitted to TJ can hire the services of TJTestPrep or a variety of other providers. TJTestPrep’s own promotional data boasts an admit rate of 81% for those who used their services compared to TJ’s overall admit rate of 17%. Their online, self-paced class costs $599. Out of 3,160 total applicants for TJ’s class of 2022, only 336 of those who applied received free or reduced lunch and only 7 out of 485 admitted students received free or reduced lunch. The socioeconomic disparities are clear.

Under the new admission policy, each middle school receives 1.5 percent of their eighth-grade population in seats, and students are evaluated based on the student portrait sheet, problem-solving essay, GPA and experience factors (economically disadvantaged, English language learners, special education, and students attending historically underrepresented middle schools). All remaining seats are given to any student determined by the admission board to be eligible regardless of middle school seat allocation. Each applicant is assigned a number with which to be identified, assuring reviewers do not know the race, gender or ethnicity of any applicant.

Coalition for TJ, a group of students, parents, and alumni, sued FCPS over the admission policy. In February, Judge Claude M. Hilton ruled that the new admission policy discriminates against Asian Americans and must end, stating that “board members sought to use geography to obtain their desired racial outcome” and later “whether accomplished overtly or via proxies, racial balancing is not a compelling interest.”

Yet, the racial wealth gap reasserts itself in the form of wealthier students being able to live in wealthier neighborhoods with better schools. For example, Sangster Elementary, ranked by US News as the number one elementary school in FCPS, only has 37.4% minority enrollment with only 3% of students being economically disadvantaged, whereas at Hutchinson Elementary, the school I attended from before AAP, ranked 105-140, has 95.5% minority enrollment and 81% of students are economically disadvantaged.

As I look around my senior classes, I see striking similarities to that of my third-grade class. The legacy of the AAP program lives well past eighth grade. Despite students being allowed to choose more challenging courses in high school, a student who was a part of the AAP program may be more likely to consider and enroll in more AP classes.

In New York City Public Schools, the largest school district in the country, the gifted and talented program is being discontinued in favor of an accelerated model that will continue to provide enrichment for students with special abilities but will not separate classrooms.

The solution does not lie in funding the programs that separate students on the basis of test scores and other subjective metrics collected when the student is between seven and eight and guarantees them access to an elite class until high school. The solution lies in assuring each child has what they need to achieve their academic potential. Possible steps forward could come in the form of after-school tutoring and homework time to assure students have a safe and quiet space to do their homework or summer enrichment activities to assure low-income students do not fall behind during the break-in compared to their high-income peers.

The AAP program helped prepare me for high school and future success, but the idea that two tests and a few other factors played such a large role in getting me where I am today is quite unsettling. The effects of gifted programs are far-reaching, and the fact that admission into these programs has fundamental, structural issues that disadvantage low-income and minority students is frightening.