Review: dark academia genre displays discrimination

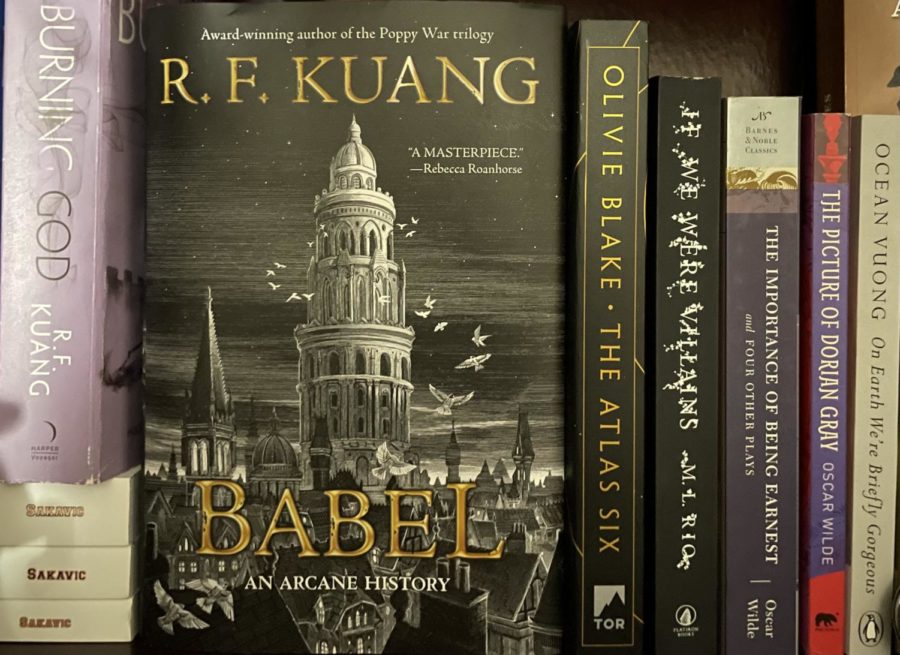

Dark academia books reside on a student’s bookshelf, including the classic “The Picture of Dorian Gray,” by Oscar Wilde, and popular novels such as “Babel,” by R.F. Kuang.

May 12, 2023

Ink stained fingers, deep eye bags, slanted messy handwriting in the margins of brown battered books and vintage lamps dimming rooms late at night are some of the many aspects that create the dark academia aesthetic. The genre is often set in 18th and 19th century prestigious institutions, colleges that have been around for hundreds of years and revolve around power and knowledge clashing against acts of violence and the morality of murder.

The main characters study late into the night, clad with tweed jackets and slacks, learning classic languages and navigating their way around an unwanted murder. The foundation of these stories surround the “must-read” classics, such as “The Picture of Dorian Gray” by Oscar Wilde and authors like Fyodor Dostoevesky, Mary Shelley and Virginia Woolf, where characters navigate ideas of justice and death. The issue lies, however, with the lack of non-western literature in this genre, leading to protagonists who are all white upper-class men.

Of every dark academia book I’ve read, not one has been set in an area other than Europe or the U.S., however, there are a number of elite institutions residing in non-western areas, such as Al-Qarawiyyin. According to the Daily Sabah, Al-Qarawiyyin is the world’s oldest operating university, founded in 859 C.E. by a Muslim woman and located in Morocco. Peking University, which ranks first in the Asia-Pacific according to Times Higher Education, is yet another example of a prestigious university.

A fan favorite of the genre, “The Invisible Life of Addie Larue” by V.E. Schwab, follows main character Addie across hundreds of years after being granted immortality in exchange for never being remembered. But, when reading the book, I was surprised to see that a life of travel was limited only to Europe and the U.S., and Addie never found the interest to go to a single country in Asia or South America.

Due to the time period, much of the dark academia genre avoids the progress accomplished by the civil rights movements across the world, leaving no room for minority voices as main characters. This leads to a glorification of the 19th century without addressing the era’s racism, classism and elitism.

Secret societies are the most apparent example of elitism; they are the main catalysts for covering up violent crimes made by those with “superior” intellect, who, of course, don’t deserve to be punished for their actions. The exclusivity of the secret societies go hand in hand with members benefitting from systemic structures that allowed them as the select few to gain membership. The opportunities are endless, however, and secret societies provide the perfect opportunity for the critique of exclusivity within academia and even rebelling against systemic structures, if only more authors explored the limitless stories within the genre.

An author who has taken strides in dark academia to go beyond the aesthetic of the 19th century and sleepless students is R.F. Kuang, who in her bestselling book, “Babel: an Arcane History of the Translators’ Revolution,” explored the intricacies of racism and classism in elite universities. Following Robin Swift, a student taken from an opioid-plagued city in China, “Babel” is a story about British colonialism perpetuated through a system of language related magic. The book uses secret societies to rebel against the eurocentrism of academic institutions, gifted students to showcase the profiting nature of western countries and multifaceted characters to comment on the intersectionality of gender and race.

As a genre having gained prominence around 2015, books like “Babel” display how dark academia has the potential to address systemic issues, and authors like R.F. Kuang, Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé, Tasha Suri, Laura Pohl and Grace D. Li are only the beginning of a genre that works to critique the flaws of society instead.

Erica • Jan 13, 2025 at 5:31 am

Does anyone have any recommendations for books set in other cultures? I was under the general understanding that Dark Academia tends to focus specifically on the vibes of Oxford, Cambridge, and Ivy League education with a very specific Western influence, usually exploring themes of privilege, competition, and hubris. I would be very interested in reading a “dark academia” novel set in a different culture though. Al-Qarawiyyin in Morocco would be VERY Interesting! I have never learned about student culture in historical Morocco before!

Another book by RF Kuang, The Poppy War, is a partially Academia novel as the MC is at her war college for half of the book, but I wouldn’t really consider it to be a Dark Academia novel.