Movie Review: the startling relevance of “Duck Soup”

Through the generations, political satire films have turned the unnerving into the comic; they have given both initiated and uninitiated audiences the chance to ponder the consequences of inane world leaders through the deriving of comedy from this very quality. The United States, over the current election cycle, has seen the success of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump (both of whom are not accepted with unanimity among their parties) in the presidential primaries. Regardless of one’s political views, it can be understood that the primaries (mostly those of the right) have been marked by a fierceness of competition and a refusal to exhibit restraint that is best exemplified by Trump’s association of enemies – on social media and in speeches – with negative adjectives: “lyin’ Ted Cruz,” for example, or “crazy Megyn Kelly.”

Though a candidate’s policies are not the same as the public persona of the candidate in question, the latter is important, and always to be taken into consideration due to what it can reveal about judgment and tenacity. This is one reason that the classic political satire “Duck Soup” (1933) could largely have been written and produced today. While not the greatest of political satires from a strictly artistic standpoint – that honor goes to Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (1964) – it is nevertheless a brilliant work of comedy, and arguably no other satire in the Hollywood classic pantheon provides such a generous amount of humor in proportion to its running time (which in the case of “Duck Soup” is a rather feeble 68 minutes).

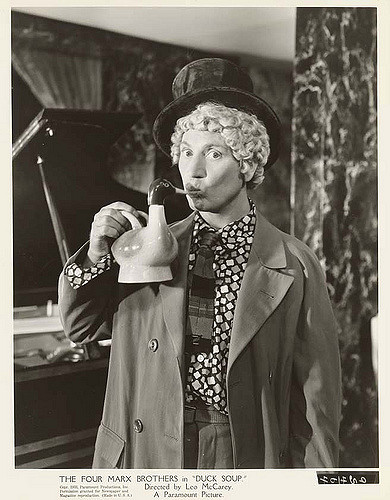

One in a line of acclaimed movies featuring the comedy troupe the Marx Brothers, “Duck Soup” follows the unpredictable and enormously incompetent Rufus T. Firefly (Groucho Marx), who, after being appointed dictator of the fictitious Freedonia, disregards one chief executive responsibility after another with increasingly unfortunate results. Probably the family act’s funniest film, humor of various forms abounds in “Duck Soup.” In the inauguration scene, Firefly merrily sends a string of insults to his assistants and subordinates. Later on, in a meeting, Firefly lists some proposals. Hardly any of them are grounded in the slightest reality.

Firefly is not insane in the traditional sense, but his ineptitude, made all the more convincing by Groucho’s carefree and rapid-fire delivery, is constant: talking so fast that it sometimes feels he is picking these proposals and one-liners out of hats, his persona is unchanged by the controversies in which it engulfs him. In “Duck Soup,” brilliance in wit couples with idiocy in political resolve; Firefly’s sheer irreverence, far-reaching and fully unapologetic, is the hallmark of the Marx brothers’ body of work.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Chantilly High School. Your contribution will allow us to cover our printing and annual website hosting costs.