Crisis at the border: students weigh in on family separation

*Sources: National Immigration Forum, The Washington Post, The New York Times, PBS News and CBS News

September 27, 2018

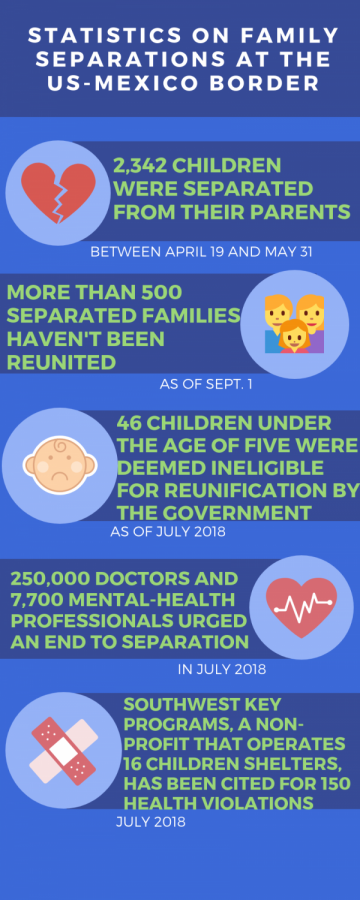

On May 7, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a zero-tolerance policy on separating children from their parents at the southwest border as a preventative measure against undocumented immigrants entering the country. The policy isolated border crossers, even those who had requested asylum, from their children. Since then, over 2,300 children have been separated from their parents, according to The Washington Post. The parents were then placed in detention centers or deported. Following public outcry over the separated minors, some five years old or younger, the Trump administration faced a court-mandated reversal of the child separation policy by July 26. Thus far, according to the New York Times, the parents of about 431 children appear to have been deported without them, and more than 400 children have yet to be reunited with their families.

Students have varying opinions about the events that unfolded this summer, especially concerning the young children and the effects of being torn away from their parents.

“A better alternative to separating families would be to process them, follow the law to make sure that you’re not just separating them, putting them in detention centers and leaving them there for six months; but follow the law and make sure they’re actually being cared for,” senior Katie Gallagher said.

Many prominent medical organizations, such as the American Psychology Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, have spoken out about the risk of potentially irreparable psychological damage on the children involved. Media coverage over the summer educated the public about what was occurring, and individuals throughout the country weighed in on social media and in conversation.

“It’s immoral to separate children from their parents, especially if they’re as young as three or four. On top of that, the detention centers don’t have resources to provide for these children and their parents,” junior Shoma Zafar said. “What the administration is doing right now is criminally prosecuting these families, but applying for asylum isn’t a crime, so it’s incredibly immoral and a human rights violation.”

Others believe that the separation was necessary, comparing the consequences of immigrants breaking the law to repercussions faced by U.S. citizens.

“The separation is justified. In a perfect world, there would be no separation, but if you think about it, they’re coming in illegally, they shouldn’t be here, and if they want to come into the country, they can come in legally,” junior Jacob Hemmerick said. “The same thing happens to actual citizens in the United States who are criminals; they get separated from their children. It is an outrageous standard to enforce strict family togetherness for people who aren’t even citizens of our country.”

People against the separation came together for a nationwide protest on June 30 to raise awareness and promote change, and critics remain outspoken because not all of the families have been reunited.

“Even if they are illegal immigrants, they’re still people, and saying that they’re illegal and not welcome in your country isn’t an excuse to have a human rights crisis,” Gallagher said. “There were some people that were protesting in their own cities, protesting family separation; they had signs and were marching the streets and saying, ‘Reunite families.’ There are also a lot of people who have been calling their senators and calling people in government and making sure their voice is heard.”

Although student discourse on the topic of child separation seems to have died down over the summer, it is still an ongoing issue, as according to The New Yorker on Sept. 13, more than 400 children are still separated from their families.