Two sides of the screen: Students, teachers must compromise for increased online participation

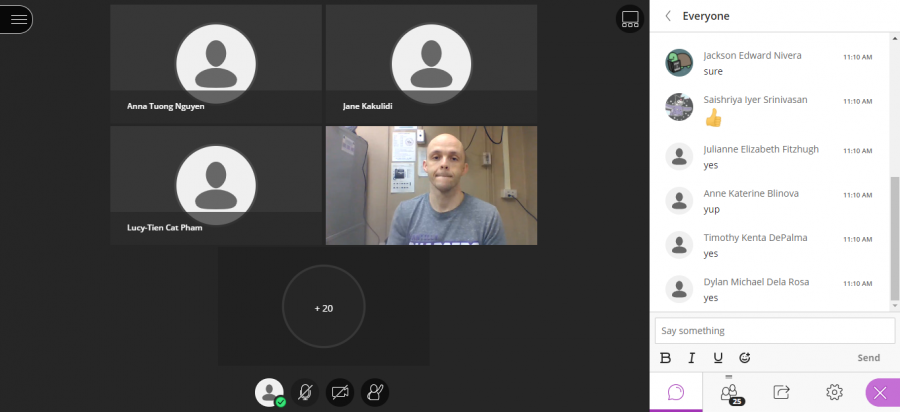

English teacher Robert Nelson instructs his students on Blackboard Collaborate Ultra on March 2.

March 20, 2021

Most students knew the online class dynamic would be different from in-person. Some thought it would be more difficult. All of them were right.

With the end of the school year just barely out of reach, loss of motivation to participate looms over students. Answering in the chat, speaking through the microphone and turning the camera on for all to see became 10 times harder than when online school first started—not that these were such easy demands to begin with.

On the other hand, teachers work tirelessly trying to encourage students to participate and become disheartened after hours of teaching to the brick wall of silence: a still computer screen with faceless name tags and the occasional but quiet “yes” and “no” in the chat box.

While every class has different levels of student interaction, most students choose not to turn on their cameras. Although some teachers would like to see nods of affirmation or looks of confusion from their students during lessons, it can be difficult for students to overcome feelings of insecurity and discomfort when showing their puffy morning faces, ungroomed hair and messy rooms. If a picture is worth a thousand words, a live video is worth a million—quite intimidating for the average, self-conscious teenager.

“We don’t turn our cameras on as much as elementary schoolers because we’re in our homes that are very vulnerable and private areas, and it’s hard to be vulnerable with people we don’t know,” senior Rabeea Khan said.

For many students, letting 30 other people hear their voice isn’t as scary as turning on their camera, but some would rather go through class on their beds, silent and unresponsive. Their microphone may pick up the yelling of their younger sibling, or they may feel as if they’re interrupting the lesson.

“I think what often happens is, if I’m talking and students try to come in, there’s an overlap in the audio and they try to avoid it,” math teacher Annie Chong said. “I think some students are so nice that they don’t want to be rude, so they often just mute themselves even if they want to talk.”

Still, the lack of active responses from students comes with consequences—for teachers especially. Teaching to the void day after day can be monotonous and demoralizing, causing teachers to lose motivation. English teacher Robert Nelson’s ideal online situation includes all students turning on their microphones and cameras, even though reality inevitably differs.

“I don’t see anybody or hear from anybody—other than the specific students who consistently participate [whom] I’m grateful for—so it’s a little bit of a bummer to not see you guys and not know if people are there and engaged,” Nelson said. “Mandating cameras and microphones makes pushing students to get stuff done in class a little more accountable and easier [since] someone is looking at you and someone can remind you that you’ve got to get back on track.”

The pressure for students to directly engage in their learning process and for teachers to find more effective methods of instruction only increases in the transition to hybrid learning.

“Students’ attentions are being pulled in so many directions that it’s sometimes easy to lose focus on the fact that this is school and they’re here to be educated, which means they’re here to hone skills, which means they’re here to feel much more efficacy and confidence in their abilities to do and think in certain ways,” Nelson said.

At the end of the day, some teachers just want to hear from students through the chat, regardless of what is said.

“If you at least give a wrong answer, it still means you’re listening and trying to do the problems,” Chong said. “I would really like to encourage students to ask questions and to not be scared of getting them wrong. Trust me, you’re helping the teacher by talking and throwing out wrong answers.”

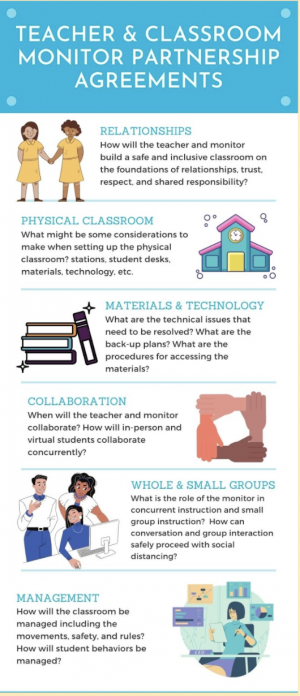

Unfortunately, mustering the confidence to interact with others and learn collaboratively can be daunting, especially in an online class filled with unfamiliar peers. However, when teachers aim to build a sense of community, breaking the silence becomes just a bit easier.

“I’m most comfortable participating in my economics class [because] my teacher starts the class with pleasantries,” junior Krishna Bhamidiphati said. “Mr. Clement really wants to know what is going on in our lives and make a really casual class setting. Just by him making connections with us and being upbeat about what he does, I really enjoy the class.”

Ultimately, increasing the overall level of student participation—whether it be just 10 more students typing in the chat or every student confidently turning their cameras on—requires group effort. The silence will only continue unless it is acted upon by both students and teachers.

“If I was the only one with my camera on, it would be really awkward,” Bhamidiphati said. “But if the whole class were to do it, I would do it in a heartbeat.”