Staff Editorial: LGBTQ+ books should stay in school libraries

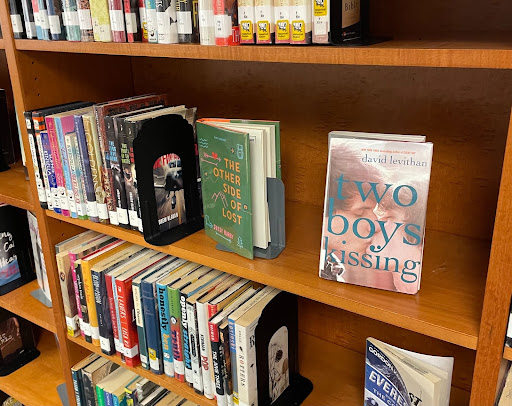

Many LGBTQ+ books are still available at the school library for students to check out.

November 10, 2021

Explicit scenes have no place in a school library, especially if they are between two people of the same gender. This belief led two Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) parents to speak up against graphic LGBTQ+ books in school libraries at the Sept. 23 school board meeting. Their concerns were met with approval from most audience members, who refused to quiet down until the board was forced to clear the room for a five minute break from proceedings.

There haven’t been concerns raised in the past regarding overly graphic books—until those books portrayed LGBTQ+ themes. Suddenly, parents believe that these books are harmful to young audiences and must be removed from school libraries.

One book brought up during the meeting is “Gender Queer,” a memoir by Maia Kobabe. The author—who goes by the pronouns e/em/eir—writes about eir experiences as being non-binary and asexual, describing eir path to self-identity and acceptance.

The story is relevant to high school students, especially those who struggle with the same things Kobabe did. A study by the University of California reveals that LGBTQ+ students exposed to queer media had a higher emotional response of happiness and hope than ones that didn’t. Keeping stories like Kobabe’s in school libraries normalizes the experiences that many students live through and provides a sense of validation for these students.

Though this book does contain scenes of sex and masturbation, it depicts natural aspects of many teenagers’ lives. Similar graphic scenes are also present at the library in heteroromantic books such as the Twilight Saga. Removing LGBTQ+ books could make students feel ashamed of their natural emotions and experiences.

Jonathan Evison’s “Lawn Boy,” also brought up in the meeting, depicts a man reflecting on a sexual encounter between him and a classmate in the fourth grade. Although this isn’t pedophilia—as was claimed at the school board meeting—the scene may be seen as disturbing or uncomfortable due to the age of the characters.

Still, just like Kobabe’s story, his journey to self-acceptance is one that students may identify with and thus deserve a chance to read. If sexually explicit scenes like this bother students, they can simply read one of the other 20,000 books available to them in the school library.

LGBTQ+ books available without sexual themes include “Ask, Tell” by E.J Noyes and “It Gets Better” by Dan Savage, among others. On the other hand, those who are comfortable with these scenes should have the right to read “Lawn Boy” and any other book that they want.

Although “Gender Queer” and “Lawn Boy” are far from the only LGBTQ+ related books available in the school library, their removal isn’t harmless. A study by a professor at the University of San Diego found that “media depictions of LGBTQ+ youth have been scarce” and lead both heterosexual and queer youth “to believe LGBTQ+ people are not an important part of society.” For decades, the nation has made progress with inclusivity and acceptance of all sexual and gender identities. Taking these books away from students represents a larger trend of reversing progress and repressing ideas that should be spoken about and shared.

Everyone deserves access to the books they want to read. Reading books helps students learn more about themselves and the world, and students’ choices shouldn’t be limited by the school board. Instead of silencing queer voices, schools should promote books that educate students and normalize conversations about LGBTQ+ experiences.