Apples and oranges: Jokes using unwanted produce reveal school food waste issue

Over 20 oranges litter the ground under the stairs to the modulars on Dec. 13. As of Jan. 19, only two oranges remain.

January 29, 2022

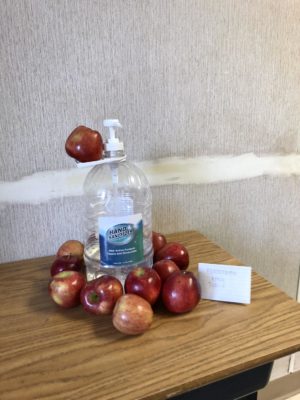

Instead of finding their way into the stomach of a happy Charger, apples and oranges are ending up scattered under the stairs to the modulars and stacked in pyramids inside of bathrooms.

Since the beginning of the school year, students have been using leftover or unwanted fruit from the cafeteria to make these displays in numerous locations.

“There are oranges in a place you wouldn’t expect oranges, and somebody is maintaining it too because they’ve been there for months now,” senior Alexander Ketzle said. “It’s funny. [The people behind it] probably do it because they’re bored.”

Freshman John Powers confessed that he was one of the students behind the shrines of apples and oranges around the school and expressed his motives.

“[The culprit] is really silly and likes wasting fresh produce,” Powers said. “[They] are trying to make beautiful art to beautify our school and have more people in a positive area. [The stacks of fruit] are a memorial to how you can always have a fresh start and stack on top of something else.”

Many students complain about the cafeteria fruits’ quality: a prime reason why students joke around about the food rather than consume it.

“The oranges are stale, hard and about as edible as baseballs,” senior Jessica Yang said. “The apples are slightly better than the oranges—not to compare apples and oranges—but when you eat them, you still get the sense that they’ve been left out for a long time.”

The Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) free meal program enacted during the pandemic contributes to the uneaten fruit. Students must take at least three out of either milk, grains, fruits, vegetables and meat or alternative meat in order for their meal to be free of charge, conforming to the U.S. Department of Agriculture requirements.

“Expecting kids to take free fruit and eat it when they don’t want to eat fruit and will just throw it away is nonsense,” senior Shreya Chandran said. “I understand that [the school] wants to keep us high schoolers nutritious and healthy, but I’m not going to eat it.”

Although the jokes using fruit are made without harmful intentions, 530,000 tons of school food is wasted per year in the U.S., as estimated by the World Wildlife Fund in 2019.

In an effort to bring more attention to this issue, juniors Gabriel Cha and Steven Weaver collected around 200 unwanted apples and oranges from students in the cafeteria on Dec. 17 to organize the produce into a Christmas tree arrangement outside with the message “An Ode to all the Wasted Fruit” on top. According to Cha and Weaver, the day’s count of fruit was only about a fifth of what the students waste in a week, based on the totals they collect each week.

“This much fruit shouldn’t be wasted,” Cha said. “It should be going to places that actually need it like food banks and such.”

Composting in school gardens, installing sharing tables where students can take food others don’t want and increasing the length of lunch periods are some of the various ways to reduce food waste, according to the Natural Resources Council of Maine. The CHS administration has considered setting up donation tables where students could offer unwanted food items right after coming out of the lunch line. However, COVID-19 poses obstacles.

“We should be able to organize a donation table, but there are rules around everything, especially when it comes to food,” assistant principal Tim O’Reilly said. “Let’s say you go to the McDonald’s drive-thru, but they hand you the wrong bag. When you hand it back, they’re supposed to throw it away and remake the whole thing.”

Some students argue that the school should reduce the amount of produce that is ordered to meet the low demand, but since FCPS purchases food in bulk for all schools using federal funding, there is little room to adjust the supply, according to O’Reilly.

“I don’t think [reducing food waste] is as simple as changing the construct of the meal,” O’Reilly said. “It’s about what to do after. If you get something that you don’t want, take it upon yourself and take it home or make it a point to collect it.”